© 1979 Sidney Harris. Reprinted with permission from Sidney Harris. All rights reserved. |

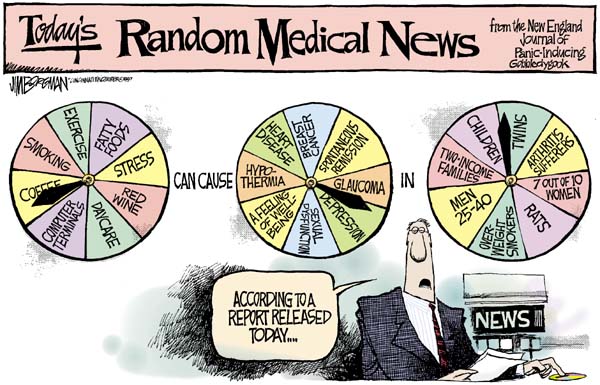

"Scars" May Be Cancer Predictor Two Drinks a Day Keep Stroke Away Weighing the Risk of a Diabetes Cure Persistent Heartburn Is a Cancer Warning Sign The Side Airbag Controversy Children Not Getting Lead Tests, Study Says Study: High Fiber Diets Donít Cut Colon Cancer No Link Found Between Fat, Breast Cancer Despite Warnings, Toxic Shock Still a Killer Home Radon Risk Not So High, Study Hints (Source: USA Today in early 1999) |

You're not alone. Advances in science and technology continue to increase the amount of health information available to the media and public. This guide seeks to help consumers evaluate health and scientific information and consider how the information can be used to improve their lives in the Age of Risk Management. Check out this online Consumer's Guide to Health Information or print it (PDF). If you enjoy this guide, then get more insight and humor from Dr. Thompson's book Risk in Perspective: Insight and Humor in the Age of Risk Management.

A Consumer's Guide to Taking Charge

of Health Information

Most people are on their own as they evaluate health information, put it into context, and make important health care decisions for themselves and their families. This requires an understanding of the concept of risk. Risk is important because it implies that there is some chance that something bad might happen. The uncertainty can be frustrating and frightening, but it also means that your attitude and choices can play a major role in your future health. The best advice you might get when it comes to making sense of health information is ASK QUESTIONS! Check out a list of 10 questions designed to help you turn health information into clues and to get you started on becoming your own health risk detective.

10 Questions & Reasons for Asking (Click here for PDF file of the guide)

| 1.

What is the message? Get past the presentation to the facts. 2. Is the source reliable?

3. How strong is the evidence

overall? 4. Does this information matter?

5. What do the numbers mean?

|

6.

How does this risk compare to others? Put the risk into context. 7. What actions can be taken to

reduce risk? 8. What are the trade-offs?

9. What else do I need to know?

10. Where can I get more information?

|

Get past the presentation and to the facts. Consider that:

- Sources personalize information to make it more interesting, but not everyone relates to the same things.

- Your perception of information can depend on whether it is presented as positive (half-full) or negative (half-empty). Flipping the statements and looking for alternative ways to state them might change your perception. For example, if you hear about a small number of people being affected, remember that this means a large number are not affected, and vice versa.

- When the facts seem confusing, keep in mind that you might have been

given false or incomplete information or you may have misunderstood

the information given.

Information comes from many sources, good and bad. Think about the information's quality. Consider that:

- All sources have a motivation for providing information. Try to identify the source and its funding so that you can consider any possible biases. The fact that a source or its source of money may benefit from the information does not necessarily mean that the information is false.

- Health information can be based on untested claims, anecdotes, case reports, surveys, and scientific studies. Scientific studies, which take samples and apply the results to the whole population, often provide the best clues about health. Nonetheless, many studies are needed to be confident about an answer. Below are some factors that might help you judge the information:

| Less Reliable

(less certain) One or a few observations Anecdote or case report Unpublished Not repeated Nonhuman subjects Results not related to hypothesis No limitations mentioned Not compared to previous results |

More Reliable

(more certain) Many observations Scientific study Published and peer-reviewed Reproduced results Human subjects Results about tested hypothesis Limitations discussed Relationship to previous studies discussed |

Back to 10 Questions

3. How strong is the evidence

overall?

Understand how this information fits in with other evidence. Some sources generally strive to provide unbiased coverage, while others may be intentionally biased. Consider how many sides of the story you hear and whether your source tells you about all of the possibilities, and the weight of the evidence.

Remember that extensive coverage of a story can be misleading if it does

not reflect the amount of evidence that supports the claim. In particular,

the results of early studies can turn out to be right or wrong after time.

Americans have mistakenly rejected results that later proved true, and

accepted results that later proved false.

Back to 10 Questions

4. Does this information matter?

Determine whether the information changes your thinking and leads

you to respond. Just because information appears in the media does

not mean that it affects you or someone you care about. Some newsworthy

risks (like accidents and homicide) may be overreported in the news media,

while other, less newsworthy risks (like heart disease and stroke) may

be underreported. The result is that you might be led to worry about small

risks that appear to be big and to ignore big risks that appear to be

small.

Back to 10 Questions

Remember that understanding the importance of a risk requires that you understand the numbers. Information about health risks gives the chances of an outcome occurring. To avoid confusion, put the numbers into a format that you can understand. Remember that you can also write 1 in 100 as 1%, ten thousand out of a million, 0.01, 1x10-2, one penny out of a dollar, or 10 in 1,000.

Researchers report their findings as expected values within a range. The breadth of the range shows how confident they are about the results. When only one number is reported, it is probably pulled out of a range and it does not inform you about the researcher's confidence in the result. In such cases, it is important to understand whether the number reflects the worst case, the best case, or something in the middle.

Remember that risks change with time, and that some people have higher or lower risk numbers than other people. Think about any habits or behaviors you have that put you at a higher or lower risk for a particular outcome.

6. How does this risk compare

to others?

Put the risk into context. One important skill for comparing risks

is making sure that comparisons all involve the chances of the same outcome,

like death. For example, the following numbers of U.S. deaths per year

per 10 million people all compare deaths per year:

| 200,000 | from heart disease (people over 64) |

| 6,000 | from lung cancer |

| 3,000 | from accidents |

| 1,000 | from homicides |

| 400 | from accidental poisoning |

| 20 | from train accidents |

| 2 | from lightning |

Since numbers about risk can be presented in many forms (like the chances of dying from a cause over a lifetime, during a year, or during an event), make sure you compare similar forms. Consider that reporting different parts of a range for different risks (best case for one vs. worst case for another) can be very misleading.

Finally, in making comparisons, other factors may be important to you.

For example, consider the extent to which you

| · | Think the risk is new |

| · | Choose the risk |

| · | Can control, manage, or prevent harm |

| · | Gain things you want by accepting the risk |

| · | Fear the risk |

| · | Feel anxious from lack of knowledge |

These factors might mislead you sometimes. For example, an unfamiliar chemical like dihydrogen monoxide might sound threatening, even though it is simply another name for water.

Remember that science can not answer the question "Is it safe?" for anyone.

You must decide what is an acceptable risk and make health decisions based

on your personal judgment.

Back to 10 Questions

7. What actions can be taken

to reduce risk?

Identify the ways that you can improve your health. Be creative.

Think about actions that can reduce your risk. For risks that are new

to you, take the time to think about them before forming an opinion. Keep

in mind that just because someone you know picks one action does not mean

that the same action will be right for you.

Back to 10 Questions

Make sure you can live with the trade-offs associated with different actions. Every decision involves trade-offs. When talking about medications, trade-offs are often called side effects, like when the medicine you take to get rid of your headache upsets your stomach. Ignoring potential trade-offs when considering an action to reduce or eliminate a risk might ultimately put you (or someone else) at greater risk.

Taking action can also lead to trade-offs of other important resources,

particularly time and money. Some people object to the idea that they

might be asked to trade between health and money or other factors. Most

people make these choices automatically, however, by driving slower at

the cost of a few extra minutes or spending money to buy a bicycle helmet

for their child or a smoke detector for their home. Remember that resources

spent to reduce one type of risk are not available for other activities.

Back to 10 Questions

9. What else do I need to know?

Focus on identifying the information that would help you make a better

decision. Remember that scientific information is always somewhat

uncertain even if it is not reported that way. Think about what information

is missing and how you would use more information if you had it. Keep

in mind that if you rely on the headlines as a basis for managing your

health, you are likely to overlook the well-established (and consequently

not newsworthy) strategies for improving your health.

Back to 10 Questions

10. Where can I get more information?

Find the information that you want. Try:

-

· Your health care provider

· Manufacturers and manuals or labels that come with their products (my recommendation is that

you actually take the time to read these!)

· Libraries

· Your original source

· Your local Department of Health

· Government agencies (many linked from www.consumer.gov)

Consumer Product Safety Commission

Department of Agriculture

Department of Health and Human Services

Department of Transportation

Environmental Protection Agency

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

· Consumer groups

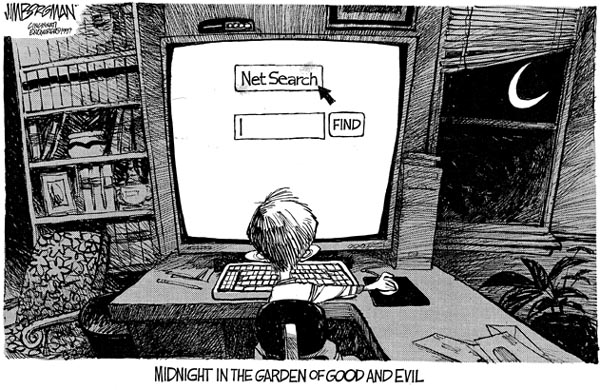

· The Internet.

© 12/4/97 Jim Borgman, Cincinnati Enquirer. Reprinted with special

permission of King Features Syndicate.

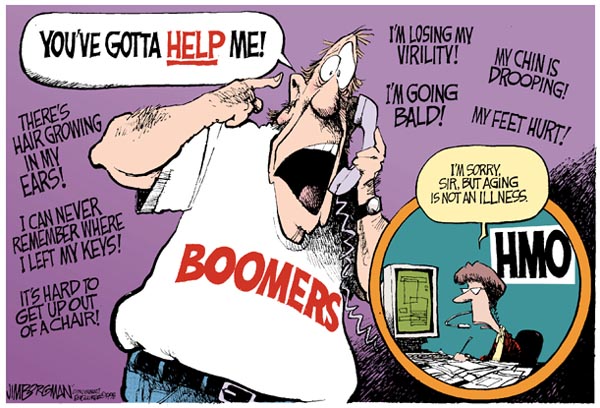

© 12/4/97 Jim Borgman, Cincinnati Enquirer. Reprinted with special

permission of King Features Syndicate.

-

· Get a copy of Risk In Perspective: Insight and Humor in the Age of Risk Management!

Harvard School of Public Health, 677 Huntington Ave., 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02115

For more information about this completed project, please e-mail Dr. Thompson.

© 1999, 2004 Kimberly M. Thompson. This guide provides an excerpt from the book Risk In Perspective: Insight and Humor in the Age of Risk Management by Dr. Kimberly M. Thompson, which is also available from www.AORM.com or Amazon.com. Development of this guide was funded in part through an educational grant to the Harvard School of Public Health from the Chlorine Chemistry Council.